编者按

深圳大学外国语学院立足改革开放特区窗口、新时代先行示范区和国际化标杆城,永葆“闯”的精神,“创”的劲头,“干”的作风是我们的底色。学院秉承“语通中外,读懂世界”的院训,践行“铸中国发展之魂,育涉外核心之才”教育使命,立足湾区,胸怀祖国,放眼世界,借新时代外语学科创新转型之势,以新文科建设为指引,夯外国语言文学之基石,扩交叉学科之视野,拓外语赋能之潜力,以“外语+区域国别”“外语+国际传播”“外语+国际组织”“外语+国际经贸”“外语+……”等为抓手,坚持“厚基础、宽口径、差异化”发展路径,培养以“外语赋能”为特色的国际复合型人才。

本着“教研并重、科研强院”的理念,着力打造学科品牌,促进内涵式发展,我们特此推出“科研荟萃”专栏,宣介学院资深教授和青年才俊的代表性科研成果和重要科研学术活动,以期打造一个既“语通中外、读懂世界”又“启迪智慧、温润心灵”的学术空间站,从而促进科研学术的引领指导和交流融通,树立深大外院坚实的科研品牌。

作者简介

Jeroen van de Weijer,耶鲁安教授著述丰富,发表的著作涉及优选论、日语语言学、荷兰语语言学、中国语言学等诸多领域;编著了《优选论:音系、句法和习得》(2000年,牛津大学出版社)等22本语言学著作,出版于Mouton de Gruyter、John Benjamins等国际权威出版社;发表了35篇同行评审文章,在一流学术期刊发表;受邀在29本语言学著作中撰写相关章节,其中2001年至2010年连续十年为牛津大学出版社的权威刊物The Year’s Work in English Studies撰稿;23次被邀请在国际性学术会议上作演讲嘉宾。他与欧美和亚洲各国的语言学家均保持着长期而深入的合作。在过去的五年里、发表文章的被引用次数达到1000多次。

Jeroen van de Weijer教授

代表作:

1.Gender identification in Chinese names.Lingua(SSCI).doi:10.1016/j.lingua.2019.102759

2.Words are constructions, too: A construction-based approach to ablaut reduplication in English”. Linguistics (SSCI), doi: 10.1515/ling-2020-0169

3.“Where now with Optimality Theory?” Acta Linguistica Academica (SSCI), doi: 10.1556/2062.2019.66.1.5

4. “Vowel reduction in English -man compounds”. The Linguistic Review (SSCI), doi: 10.1515/tlr-2019-2040

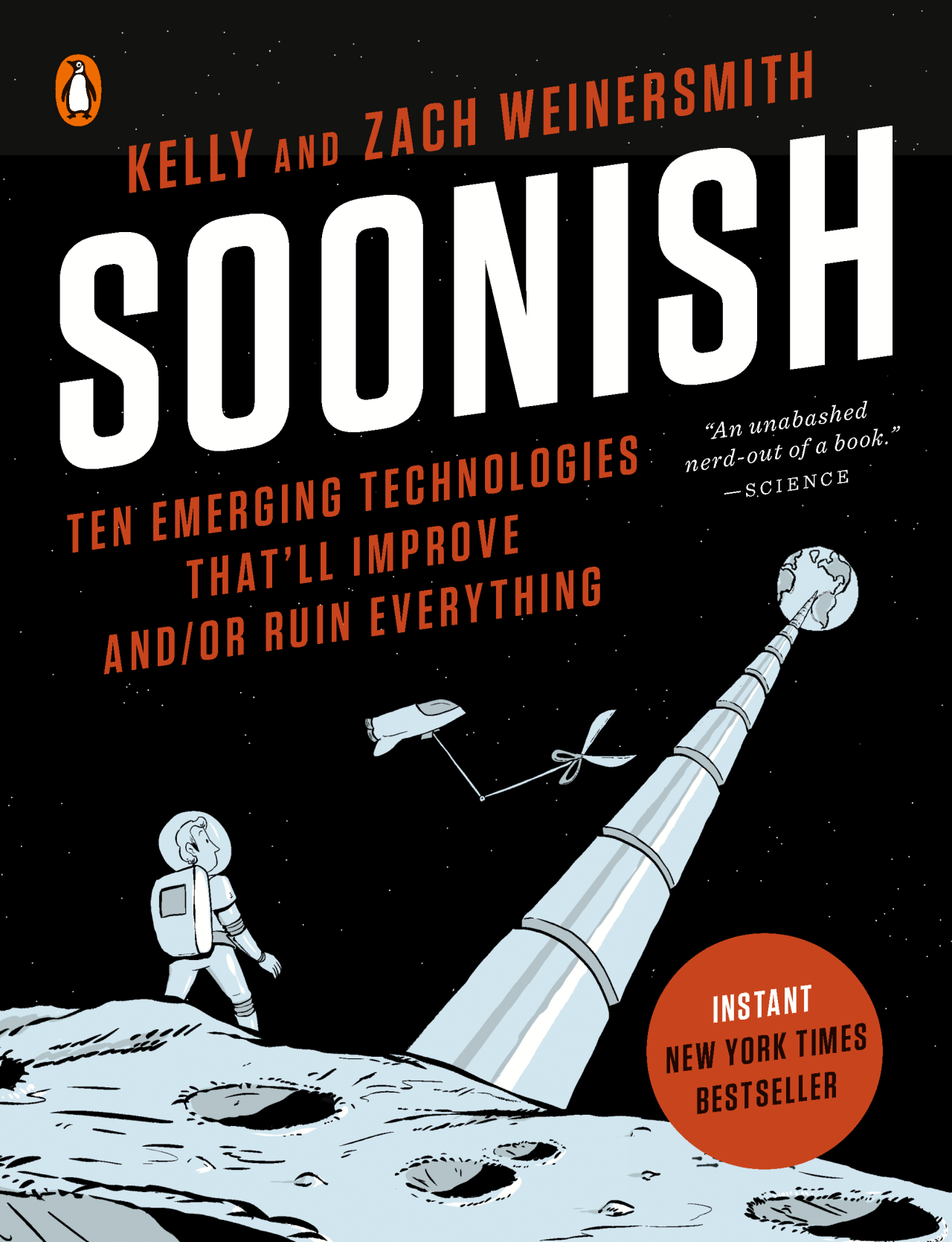

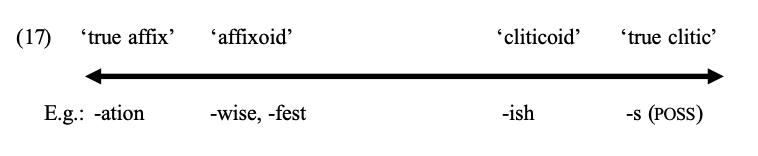

5.Optimality Theory: Phonology, Syntax, and Acquisition. Oxford: Oxford University Press (co-editor), ISBN 0198238444 nd present new evidence from historical and contemporary sources. In morphological theory, this can be interpreted as regarding -ish as a ‘cliticoid’, one step away from a true clitic on the affix-clitic continuum.

OnDeverbal Adjectives

with -ish in English

Abstract:This paper considers the evidence that the English suffix-ish(e.g.yellowish, baldish, ticklish, fivish, childish) can be attached to verbs, making it more clitic-like than a true affix. We discuss competing hypotheses in this light and present new evidence from historical and contemporary sources. In morphological theory, this can be interpreted as regarding-ishas a ‘cliticoid’, one step away from a true clitic on the affix-clitic continuum.

Keywords: English; morphology; -ish; attachment to XP; cliticoid; exceptionality

1. Introduction

The suffix-ishin English attaches to a wide range of word classes. It can be attached to nouns (1a), colour adjectives (1b) and other adjectives (1c), but also to, numerals (1d), adverbs (1e), and even some prepositions or particles (1f):1,2

(1) a. childish, amateurish, feverish, waspish, girlish, foolish,hawkish, thuggish,bookish, wonkish

b. yellowish, bluish, whitish, blackish, purplish, pinkish, reddish, greenish

c. baldish, smallish, tallish, dullish, sweetish, newish, youngish,oldish

d. fivish, tennish, fortyish, 1984-ish

e. soon-ish

f. downish, uppish, offish, outish

In nouns (1c), there is some competition between the suffixes-ish, -y(e.g.waspy, foxy, batty),-like(birdlike, lamblike) and other suffixes (Malkiel 1977), which will not concern us here (see also Dixon (2014: 240)). Malkiel (1977) also observes that-ishconveys different degrees of pejorativity, which seem to be confined to (some) nominal constructions, such aschildish. See also Plag, Dalton-Puffer & Baayen (1999) and Eitelmann, Haugland & Haumann (2020) on productivity among different word classes and historically. To illustrate its broad spectrum of usage, a list of further examples of adjectives with-ishis given in the Appendix.

Thus,-ishcan be attached to nouns, adjectives and minor word classes. In most cases it derives adjectives or adverbs with an added meaning of ‘approximate, rather, moderately’. The affix also appears in words denoting nationality adjectives or languages (e.g.English, Turkish, Spanish) or a particular kind of speech (gibberish). We will regard this as the same suffix, although its meaning here (“related to, like”) is different from the meaning of the-ishin (1); nothing hinges on this decision, and we may also regard them as separate morphemes that are part of one “morphological constellation” (Joseph & Janda (1986), cited in Janda & Joseph (1989)) (see also below). Meaning differences in what are generally regarded as the same morpheme are not uncommon, as a result of semantic drift or other reasons: compare, for instance, the differences in meaning of the suffix-ationin words likefortification, publication,anddemocratization.

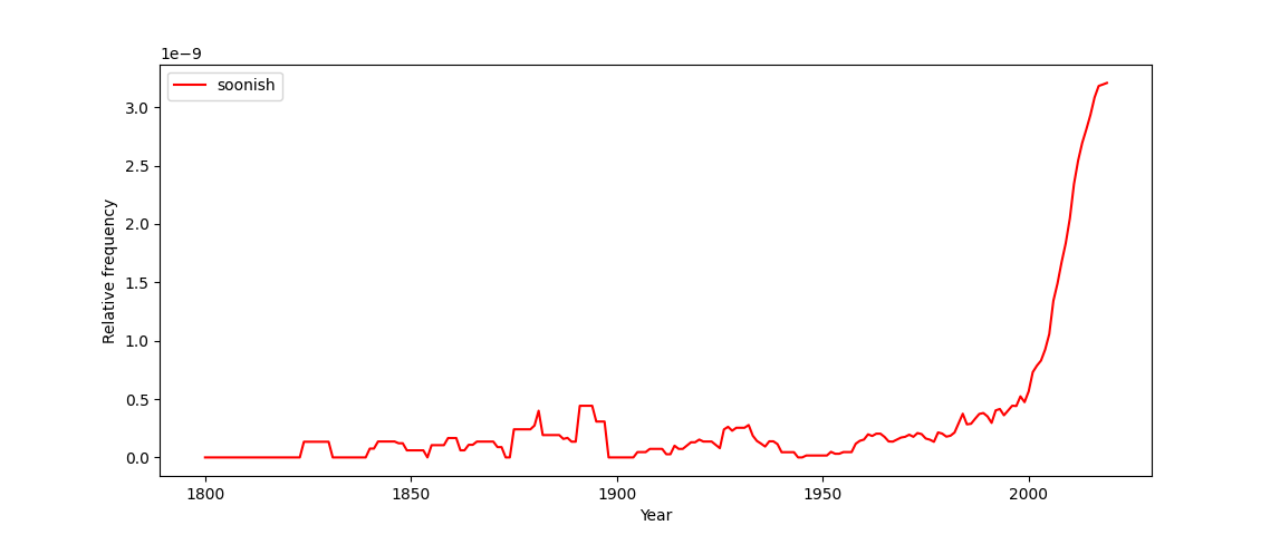

Although-ishis etymologically derived from the Old English suffix-isc, and has therefore existed in the language for a long time (see especially Eitelmann, Haugland & Haumann (2020), who present a detailed corpus-based outline of the history of the suffix), our intuition is that the popularity of-ishhas increased especially in the last few decades.3To illustrate, consider the development of ‘soonish’ (though note that the rise of this word may be specific for this lexical item, and we also surmise that competing forms with-y(cf. above) are rising in popularity: further corpus research is necessary), as visualized in Google Ngrams:4

Figure 1: Soonish, English, 1800-20195

The fact that-ishattaches to a wide variety of word classes (see (1)) raises the question whether-ishcan also be attached to verb forms. This is the main topic of the present contribution. Secondly, if-ishcan be attached to any word class, the question should be raised whether it should be regarded as a phrasal affix (or clitic) rather than a lexical suffix, i.e. more like genitive -s in English (e.g.the Queen of England’s crown) than the third person singular-s(e.g.he sleeps). In other words, if-ishcan attach to all word classes and to phrasal units, its base should not be analysed as an (almost-complete) set of categories, like in (1), but can be more generally stated as in (2):

(2) [ __ ]XP -ish

This subcategorization frame makes the prediction that the suffix can be attached to all word classes but also to larger units, i.e. multi-word phrases. We will discuss the available data and draw a tentative conclusion on the basis of the evidence below.

This paper is organized as follows: in section 2 we discuss the evidence that-ishcan also attach to verbs, based on an analysis of the wordthievishin particular and other examples where this suffix appears after verb stems. Section 3 discusses the evidence for regarding-ishas a phrasal affix rather than a lexical one. Section 4 discusses the evidence in the light of morphosyntactic theory and proposes that-ishshould be regarded as a clitic-like form (a “cliticoid”), i.e. a unit on the cline between true affix and true clitic, nearer to the end of clitichood but not quite attaining it.

2. Does-ishattach to verbs?

As we saw above,-ishfreely combines with word classes of all kinds, including adjectives and nouns. This has been noted in the literature before, see e.g. Marchand (1969: 305f.) and Bauer, Lieber & Plag (2013: 311). However, attachment to verbs is rarer, e.g. Plag (2003: 96) does not include verbs among the word classes to which-ishcan be attached, and does not mention the form in (3) below. It is usually assumed that there is only one, exceptional, example of this; see e.g. Aronoff & Fudeman (2011: 134):

(3) ticklish ‘sensitive to being tickled’ from totickle +-ish

Note that-ishin this example does not have its general meaning of ‘approximate, rather, moderately’ (likegreenish) but assigns a passive meaning to the verb (in the sense that ticklish applies to the object of tickling, not the subject), and loses its connotations of conveying moderate degree (cf. (1)). There is no other formation in-ish, as far as we know, that has the same semantic properties, and in this sense this formation is indeed exceptional. But is it also exceptional in that it is the only form in which-ishattaches to a verb?

Attachment of-ishto verbs is the main topic of this section, which is divided into two parts: in § 2.1 we discuss the word thievish, and argue that it is derived from the verb to thieve (rather than the noun thief or its plural). Subsequently, § 2.2 presents a number of other adjectives ending in-ishthat are unquestionably derived from verbs. An evaluation of these forms will then be presented in §§ 3 and 4.

2.1 The morphological structure ofthievish: three hypotheses

Aronoff & Fudeman (2011: 134), based on Nida (1949: 120), raise the question how the form in (4) should be analysed morphologically:

(4) thievish

Malkiel (1977: 350) lists this form as being derived from the nounthief. Eitelmann, Haugland & Haumann (2020: 803) give the examplesgarish(see also fn. 17 below),snappishandticklishand note that attachment to verbs happens “only infrequently” (ibid.).

Forthievish, various questions arise: isthievishderived from the nounthief(following (1c)), as suggested by Malkiel, and, if so, what explains the phonological change of finalftovin the noun stem? Is there a relation with the plural of the nounthief, i.e.thieves? Or isthievishderived from the verb tothieve? We will argue in favour of the latter hypothesis, which implies thatthievishis a second case (i.e. besidesticklishin (3)) of a deverbal adjective with-ish. Specifically, the following three hypotheses will be discussed:

(5) 1.Thievishis derived from the singular nounthief, with a concomitant rule of intervocalic fricative voicing

2.Thievishis derived from the ‘plural stem’ of the noun thief, i.e.thiev-

3.Thievishis derived from the verb to thieve.

A fourth possibility is thatthievishis not synchronically derived at all, but listed as an independent stem in the lexicon, in which semantic associations exist with the (relatively frequent) nounthiefand the (relatively infrequent) verb tothieve. In that case,thievishis not derived from any noun (or any verb) and has no bearing on the question if-ishcan be attached to verbs. Although this hypothesis is attractive in the light of an Exemplar-theoretical approach to the lexicon (e.g. Frisch 2018), it can neither be proven nor disproven, and will therefore not be considered here.

The first hypothesis given in (5), in whichthievishis based on the singular nounthiefwith concomitant voicing, can easily be dismissed6. English does not have intervocalic voicing offtovin its word-level morphology; specifically, no such rule applies when the suffix -ish is attached to other nouns that end in-f, as shown by the examples in (6):

(6) a. oaf – oafish

self – selfish

b. dwarf – dwarfish7

wolf – wolfish

In the first two cases in (6a), the final-fof the stem is unequivocally not affected by any voicing rule. In the latter two cases (6b), there may be some variation, which warrants further scrutiny and these forms are discussed below. On the basis of (6a), then, the first hypothesis in (5) must be rejected: the relation betweenthiefandthievishcannot simply be considered one of derivation with an accompanying voicing rule. However, it does suggest relating the voicing alternation to other cases: could the alternation that takes place in some plurals (e.g.wolf-wolves, thief-thieves) be related to the same alternation inthief-thievish?

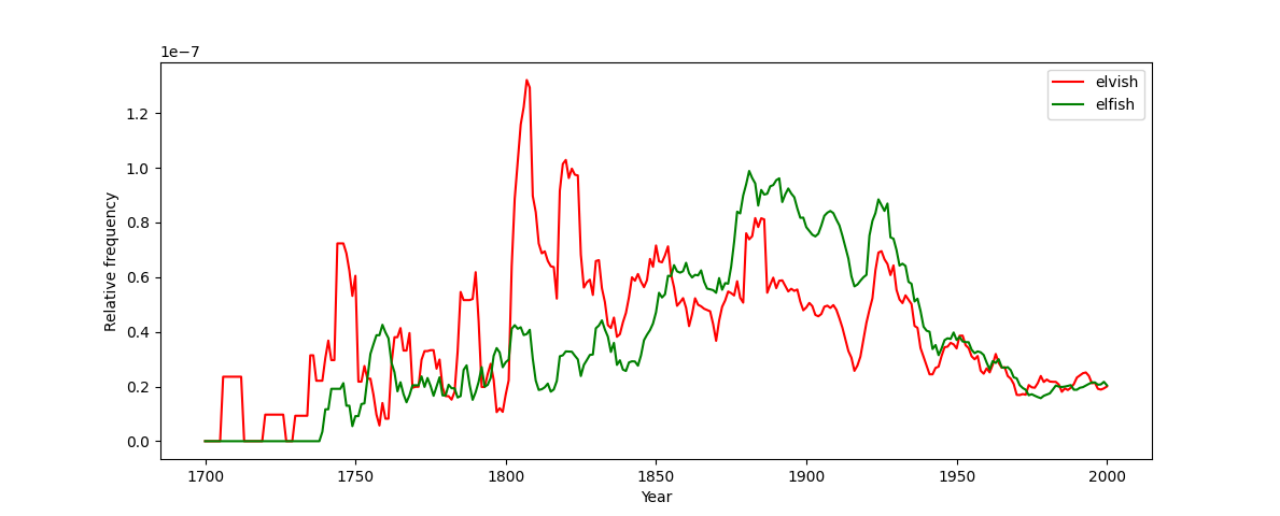

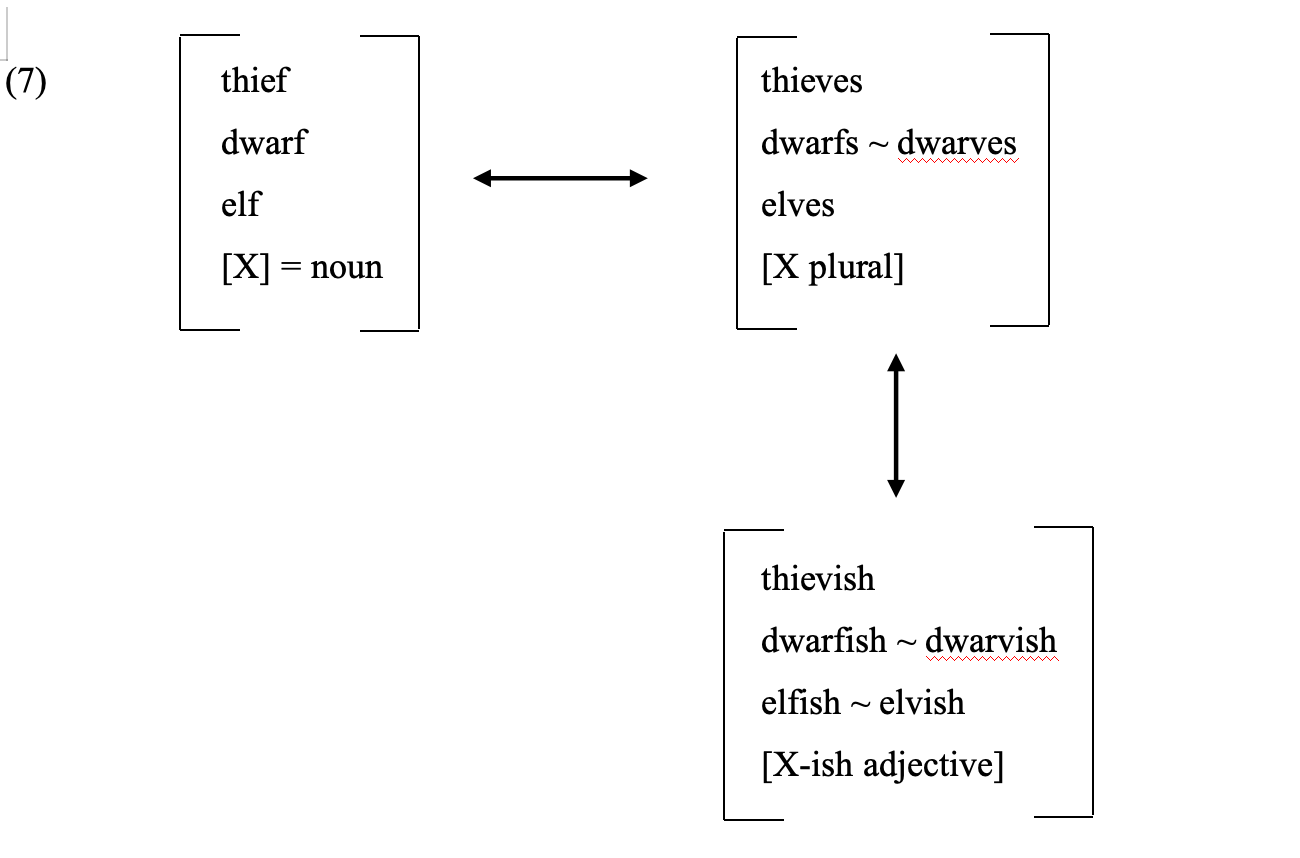

The second hypothesis is based on this idea and suggests thatthievish(and perhaps related forms likethievery) is based on the ‘plural stem’ ofthief, i.e.thiev-. This solution follows the spirit of Lieber (1982), and is essentially also what Partridge (1977: 3440), suggests (from an etymological perspective): “...thievish(fromthiefafterthieves) ...”. This is a more attractive possibility, since it does not make it necessary to postulate an ad hoc rule of f-voicing. In this scenario, we would expect the word elf, which has the pluralelves, also to allow for the related adjective elvish. In fact, bothelfish(which is typically included in dictionaries, e.g. Procter (1978) or Sykes (1982)) andelvishhave been attested throughout the history of English. Figure 2 shows that both words have been about equally frequently attested during the last 150 years, and that, before that time,elvishwas even more common thanelfish:

The fact thatelfishandelvishvary through the history of English suggests that there might be some support for the hypothesis that thievish could be related to the plural formthieves.

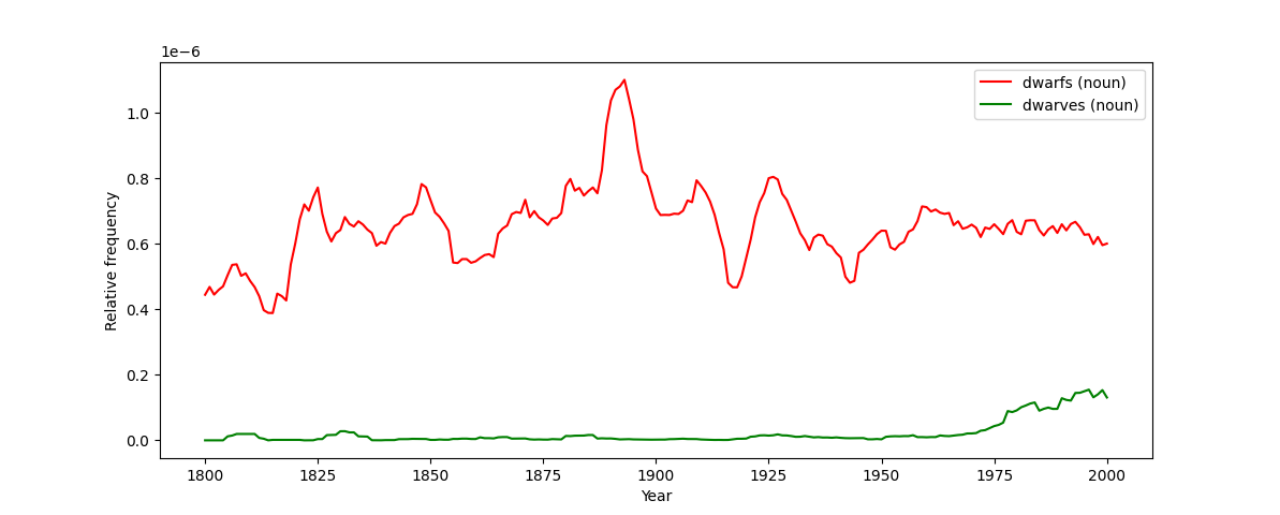

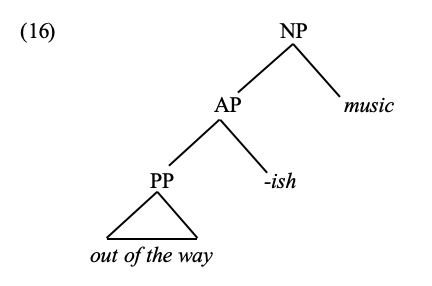

Similar toelfish/elvishis the case ofdwarfish-dwarvish. Although the regular/“standard” plural ofdwarfisdwarfs(as inSnow White and the Seven Dwarfs, e.g. the 1937 movie9), the pluraldwarvesof dwarf has become increasingly accepted, especially in British English, since J.R.R. Tolkien famously used this plural in theLord of the Rings(LOTR) saga (published in 1954-1955), and perhaps boosted by its movie version (2001-200310). Figure 3 shows the increased incidence ofdwarvesclearly:

Figure 3: Dwarfs vs. dwarves, British English, 1800-2000

Correspondingly, Tolkien used the nameDwarvishfor the language of the Dwarves (see LOTR, Appendix E: Writing and Spelling), which supports the idea that, for Tolkien at least, there is a relation between the plural (dwarves) and the adjective (dwarvish).12From a morphological perspective, such a relation could be expressed by a word-based ‘schema’ representation (cf. e.g. Haspelmath & Sims 2010: 46ff.), in which whole words form lexical patterns, without recourse to abstract units such as morphemes or rules:

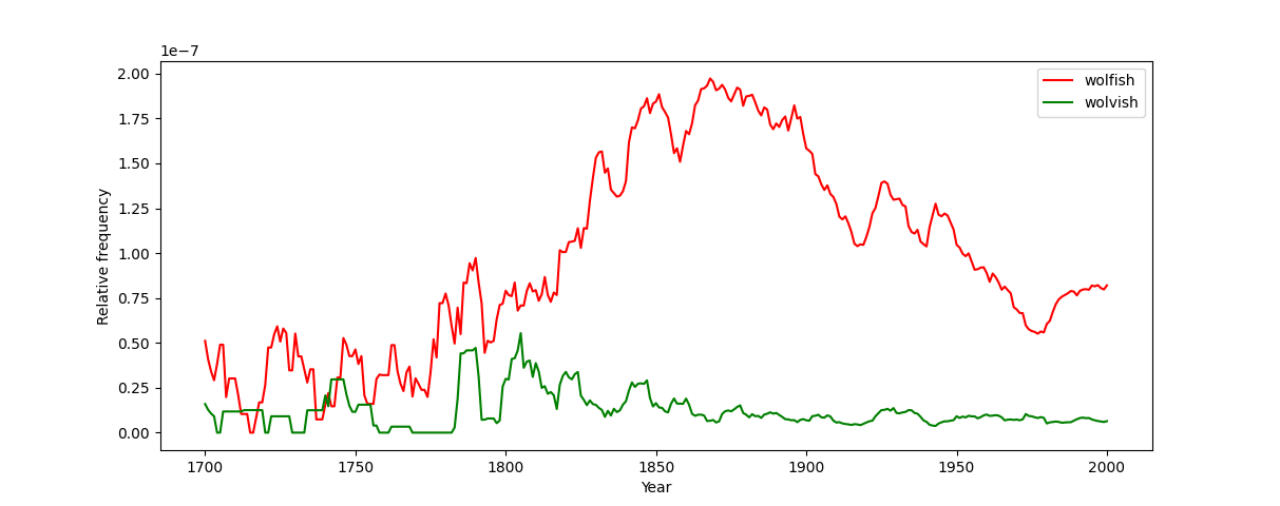

However, the hypothesis that the adjectivethievishis derived from the plural stemthievesshould also be dismissed for a number of reasons. First, as pointed out above, there is no alternative thiefish (on the pattern ofdwarfishandelfish), which would be expected if the word schema in (7) represents a correct analysis of the relations between all these words. Second, deriving thievish from the plural stem thiev- would suggest that in other plurals that have (or variably allow) plurals with v voicing in the adjective would also be allowed. However, this is not the case: for example, consider the plural wolves which under this analysis would suggest that the adjective form of wolf+ish should (or could, variably) also be wolvish.13However, this is only marginally attested since at least the early 1800s: see Figure 4 below; and see also Jespersen (1933 [2008]: 321), who suggests thatwolfishin fact replacedwolvish, which is counterintuitive ifwolvishwere acceptable in accordance with a schema like (7), since wolf only allows the plural wolves and does not vacillate likedwarfs/dwarves. An even stronger case is provided by the fact that the plural ofselfisselves, which suggests *selvishshould be possible, but this form is completely unattested. In other words, on this account there is no explanation why elf (pluralelves) allows eitherelfishorelvish(recall Figure 2), while self (pluralselves) only allowsselfish.

Figure 4: Wolfish vs. wolvish, British English, 1700-200014

We therefore also reject the second hypothesis that was given in (5) above.

Returning tothievishin (4), the third possibility in (5) is that this is based on the verb tothieve, rather than on the noun, which would make it asecondcase in which-ishis attached to a verb (recallticklish, in (3)).15This is an attractive possibility since it would obviate the need for a voicing rulef>v, which does not apply in other cases. In the verb stem thieve, the voicing of the final consonant is due to a historical (no longer productive) rule of final voicing when the verb was derived from a noun (i.e.thief(n) →thieve(v)). This rule is historically the same process that was responsible for singular-plural alternations likeelf-elves(see e.g. Campbell 1959: 179ff.). Other examples of words where this rule applied are given in (8):

(8) noun verb

house [s] - house [z]

grief [f] - grieve [v]

proof [f] - prove [v]

half [f] - halve [v]

wreath [θ] - wreathe [ð]

In this way, the voicing of the [v] in the verbthieve, and by extension inthievish, is explained by a historically uncontroversial process, and not by an ad hoc synchronic morphophonological rule.

Secondly, derivingthievishfrom tothieveis also supported from a semantic point of view, sincethievishprimarily means ‘inclined to steal’, and only secondarily ‘like a thief’ (cf. words likeamateurish, clownish, loutish, where the latter meaning is primary). Hence, a raven may be thievish:

(9) “The common raven is easily tamed, but is mischievous and thievish, and has been popularly regarded as a bird of evil omen and mysterious character.”

Oxford English Dictionary (Simpson & Weiner 1989)

To conclude this subsection, the most straightforward analysis ofthievishis to derive this form from the verb tothieve, with the meaning ‘inclined to steal’. This verb would then be another (rare) example of a verb, besides totickle(3), which allows suffixation with-ish. A closer look reveals that there are some other verbs which, even more straightforwardly thanthieve, allow suffixation with-ish. Together, these cases suggest that there is no categorical constraint against attaching-ishto verbs. We turn to these examples in the next section.

2.2 Other deverbal adjectives with-ish

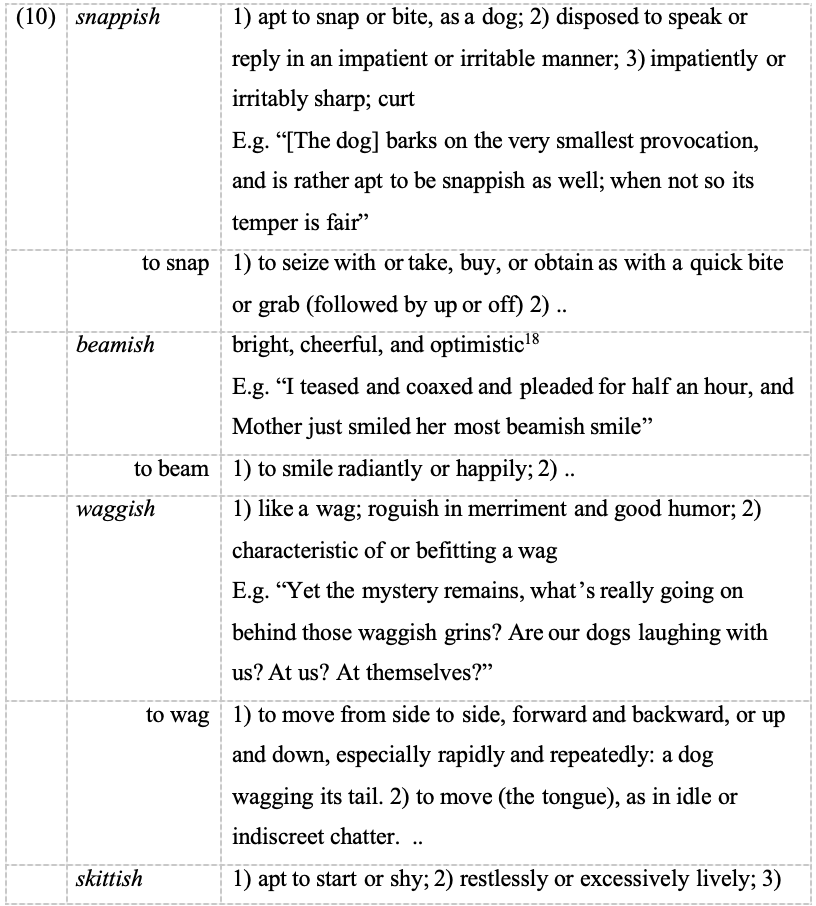

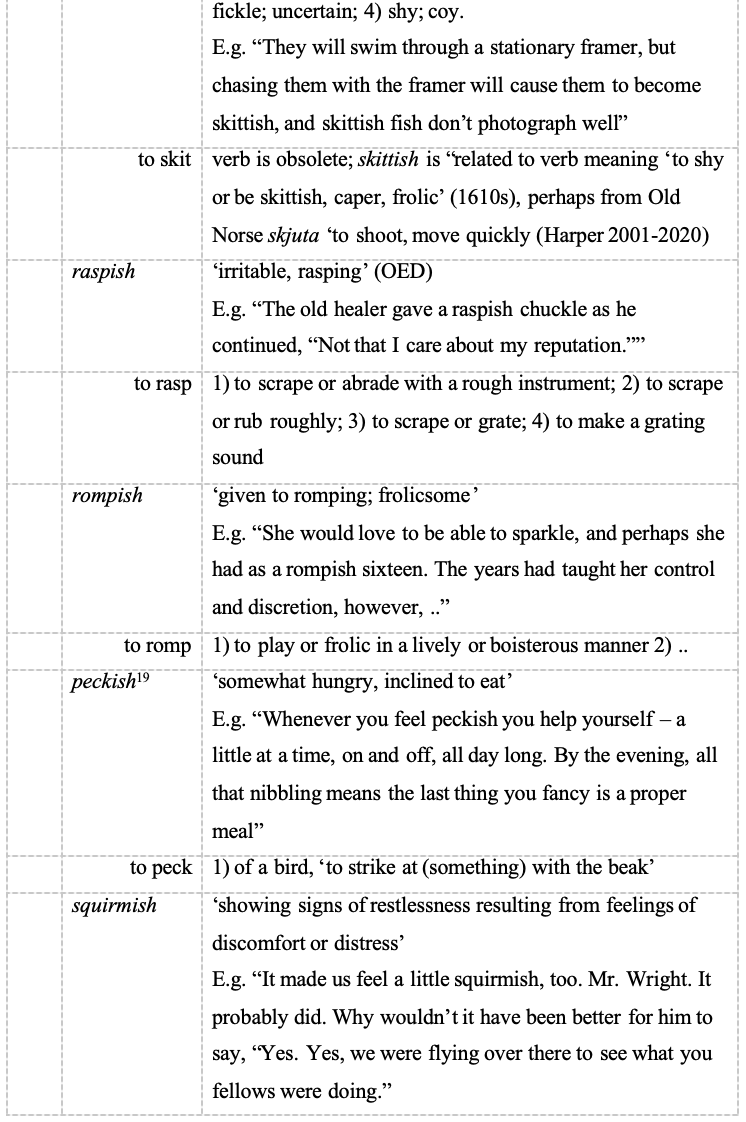

Are there other cases where-ishattaches to verbs? In fact, relevant cases are not very common but also not impossible to find. A number are listed in (10):16,17

In all these cases, the form in-ishis derived from the verbsto snap, to wag, etc., rather than from any noun (e.g. the semantically unrelated nounbeam‘long piece of wood or metal’). All adjectives also refer to a type of behaviour, so that derivation from the verb is also semantically preferable.

Note that the meaning of-ishmight be regarded as “approximative” here, like in adjectival forms such asgreenish,1984-ish, etc., but “approximative” appropriately for a verbal category, in the sense that these deverbal adjectives can be described as “likely to V / to be V-ed”. Asnappish dogdoes not snap all the time, but is just likely to do so, perhaps sometimes. Recall that we raised the question whether the morpheme in verbal cases can be regarded as the same morpheme that appears in cases such asgreenish(cf. above). These cases show that the connotation of ‘approximative’ is also present in the deverbal cases.

We conclude that-ishin a number of cases is also used to derive adjectives from verbs, so that the affix can in principle attach to all major word classes. In what follows, we assess the morphosyntactic implications of this claim.

3. Phrasal status

The fact that the suffix-ishattaches to a wide range of word classes leads us to the question of whether it should be regarded as a phrasal affix (or clitic), since one of the defining properties of clitics is that they typically attach to a wider range of word classes than affixes (Zwicky & Pullum 1983). To express this, the suffix could be attached to phrasal categories rather than lexical ones, as expressed by the subcategorization frame in (11) (repeated from (2) above):

(11) [ __ ]XP-ish

This elevates the status of-ishfrom a lexical affix to a phrasal affix, or clitic; see Klavans (1985), Anderson (1992: ch. 8), Halpern (1998), and Gerlach (2002) for discussion. While affixes typically only attach to one or a few word classes (e.g. inflectional plural-sto nouns, derivational-ento adjectives (e.g.darken) in English),-ishat first sight satisfies both the syntactic characteristics (being marked for a syntactic category, attaching to all word classes) as well as the phonological characteristics of clitics (being unstressed and needing a host to attach to). In these senses it is similar to English genitive-s, which is also argued to be a final clitic (Anderson 1992: 118-9, 202), on the basis of examples likethe boy who I saw’s mother(Gerlach 2002: 62) (see below for further discussion, § 4).

The implication of (11) is that not only is-ishpredicted to attach to all word classes (as we saw in section 2), but also to larger units. This prediction is borne out, and has been noted in the literature before: see, among others, Plag (2003: 96), who gives examples likestick-in-the-muddish,out-of-the-wayish. Below we add a number of similar examples, based on examples from modern English literature and a number of corpora:

(12)-ishadded to full names:

a. from Donna Tartt:TheGoldfinch(Little, Brown and company, 2013)

– “Oh?” I said, uncertainly, in the overly long silence that followed.

Something in his tone had made me suspect that he knew my father might be theLord Vader-ishpresence breathing audibly (audibly to me—whether audibly to him I don’t know) on the other line.

b. Ryan Chapman: Riots I have Known (Simon & Schuster, 2019)

– AnIvan Boesky-ishborn-again, transported at great expense from New Paltz’s gleaming big house on the hill to the show’s Manhattan studios, sat across from George Stephanopoulos and said, in the clear cadences of the media-trained, “I want to repay my debt to society in trade: if Iran will halt its nuclear production facilities, my fellow inmates and I will send every man, woman, and child in Tehran a delicious, gluten-free cupcake.”

c. Kazuo Ishiguro:Nocturnes(2009, Knopf)

– Her room had a Bang & Olufsen system just like mine, and soon the place filled with lush strings. A few measures in, a sleepy,Ben Webster-ishtenor broke through and proceeded to lead the orchestra.

Similarly,-ishcan be added to longer phrases:

(13)-ishadded to longer phrases:

a. Elizabeth Day –How To Fail(HarperCollins, 2019):

– It’s enough for me. As you say, it’s like having it all-ish. And that’s kind of what I’ve got. I’ve got the good career. I’ve got … You know, I know what makes me tick, which is nature and solitude and my dogs, and I have a really good marriage. …Having it all-ishis more or less where I’m at.

b. Maria Semple – Today will be Different (Little, Brown and company, 2016)

– In minutes, one of those parent volunteers would open the box, find the keys, and return them to Delphine’s mom.No harm, no foul… ish.

Examples from the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA; Davies 2008) and the British National Corpus (BNC; Davies 2004) are presented below:

(14) Examples from COCA:

a. “Amy Steel, she was just so adorable. She was sogirl-next-doorish. She would probably be my all-time favorite "Friday" girl.” His Name Was Jason: 30 Years of Friday the 13th” (Movie documentary).

b. “loathing, the grosser undercurrents of hostility, fratricidal and patri- or matricidal impulses,fox-in-henhouseishpreying on one's own potential successors, those are more like secret poxes-venereal flare-ups” (Harper’s Magazine)

c. “look at her and Vivienne. What a saint! There was nothing remotelydog-in-the-mangerishabout Beth, that was one of her special qualities. She loved Gus and ..” (Fiction:Friends for Life)

(15) Examples from BNC:

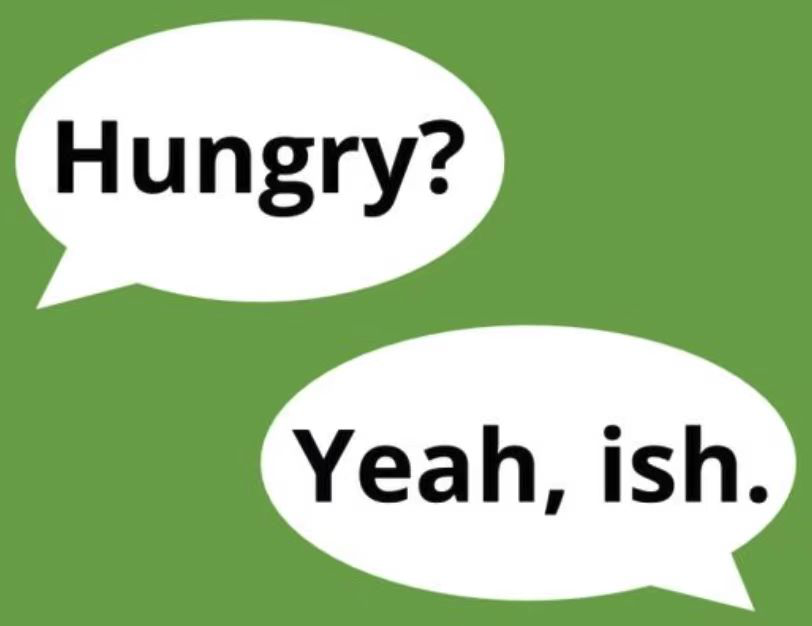

a. “The programme had some goodout-of-the-wayishmusic: notably songs by Stenhammar and Rachmaninov, and Prokofiev's brilliantly direct, inventive setting of The Ugly Duckling”. (Arts broadcast)

b. “I had to find pen and paper and write it down. I always did after a terror-dream. It was still dark,middle-of-the-nightish, but I'd scribble something -- I had to put it in my possession, take away the terror of it, put it under my control”. (Fiction:Gate-crashing the Dream Party)

c. “the best commercial of all time? Justin: No. Too messianic, tooend-of-the-worldish. And with a sensitive subject like nuclear power, the end of the world ..” (New Internationalist, Magazine)

The examples in (12-15) present clear support for the suggestion that -ish is flexible in where it may attach, as suggested by its subcategorization frame [ ]XP: in clitic-like fashion, whole phrases may be targeted. For example, the syntactic structure ofout-of-the-wayishmusic would be as in (16):

Two things to note are, first, that in none of the examples in (12-15) is there a tensed verb in the phrase to which-ishattaches: potential examples like “He is a might-makes-right-ish politician” (wheremakesis marked for present tense) are conspicuously absent. As observed by an anonymous reviewer, all these examples, as well as those in previous literature, involve names or idiomatic expressions, which are typically analysed as lacking (or having less) internal structure (e.g. Horn 2003, Nunberg, Wasow & Sag 1994) compared to non-idiomatic phrases. These idiomatic expressions could be regarded as types of constructions: see especially Traugott & Trousdale (2013: 233-7) and references cited there, for the development of this historical process with respect to-ish.

Related, attachment of-ishis not as free as the attachment of possessive -s20: next tothe boy who I saw’s mother(Gerlach 2002: 62) (see above), phrases likethe boy who I saw-ish motherare of questionable acceptability at best. No such examples are reported in the literature, nor were they found in the searches through COCA or BNC. The final section examines the morphosyntactic implications of these findings.

4. Discussion and conclusion

The suffix-ishin English attaches to a wide variety of word classes, but it has been generally assumed that it does not attach to verbs, with few exceptions. In § 2 of this paper, we argued at length in favour of the hypothesis thatthievishshould also be regarded as derived from the verb tothieve(rather than the nounthief), based on the voicing alternation and semantic characteristics. A few other examples of deverbal adjectives with-ishhave been identified in the literature such as ticklish and snappish, and other examples that could be added areskittishandsquirmish(see the list in (10) above). Thus, there seems to be no ironclad restriction against attaching this suffix to verbs, although the number of examples is not overwhelming.

Secondly, we saw that-ishqualified as a phrasal affix (suggested by the wide variety of word classes it attaches to) but its behaviour is not as “promiscuous” (Woodbury 1996: 322) as that of the prototypical English possessive clitic-s. Phrasal attachment was largely restricted to personal names and non-tensed idiomatic expressions, and a hypothetical phrase likethe boy who I saw-ish mothersounds decidedly worse thanthe boy who I saw’s mother(rated acceptable by Gerlach (2002: 62), see also Carstairs (1987)). Further investigation is undoubtedly needed here, both on the basis of corpora and on psycholinguistic experiments seeking acceptability judgements.

Thus, taking both aspects together,-ishbehaves like something more flexible (in the senses noted above, i.e. of attachment to different word classes and attachment to phrases) than a traditional affix but less so than a full-blown clitic. Following much earlier literature (e.g. Dixon & Aikhenvald (2002) and other sources on grammaticalization) we propose that the distinction between affixes and clitics (and words) is not a binary choice, but rather should be placed on a continuum, where different morphological units can occupy different points on the scale. This has been noted for “novel” affixes like-wise, -fest(e.g.cryfest, typofest, budgetwise, relationshipwise) and other items, which have been termed semi-affixes or affixoids (see e.g. Algeo (1991), Booij & Hüning (2014), Kenesei (2007)). An appropriate name for a unit on the other side of this continuum, closer to a true clitic, could be semi-clitic or “cliticoid”. This would result in a (partial and tentative) cline like that in (17):

Different remarks are in order with respect to (17): other examples of “true clitics” could be found (perhaps even truer than possessive-sin English; see Klavans (1985) and other sources mentioned above, on cross-linguistic differences in clitic placement) and other affix categories could find a place on this continuum, which needs to be further motivated.

A proposal recognizing a continuum for the affix-clitic division does not follow strict binarity, as in classical (generative) theories, but fits well with more recent, probabilistic approaches, where patterns of knowledge are not either present or absent but may vary in strength. Secondly, it suggests that the grammatical development of-ishmay be ongoing and could still move further into the direction of a full clitic, exactly along the lines Norde (2009) suggests, although any such predictions must always be regarded as tentative. We propose that the status and attachment properties of-ishin Modern English are best regarded from this perspective.

Appendix:

Words in-ish(excluding nationality names likeEnglish, Turkish,etc., derived compounds (e.g.light-greyish) and some derivatives withun-), extracted from the sixth edition ofRoget’s Thesaurus(Kipfer & Chapman 2001). Other sources may add or omit some items.

aguish, airish, amateurish, apish, Babbittish, babish, babyish, bearish, biggish, blackish, blockish, bluish, bluntish, boggish, boobish, bookish, boorish, boyish, brackish, brigandish, brownish, brutish, buffoonish, bulldoggish, bullish, caddish, carlish, cattish, charlatanish, childish, chumpish, churchish, churlish, clannish, clayish, cloddish, clodhopperish, clonish, clottish, clownish, clubbish, clumpish, coltish, coolish, copperish, coquettish, cowish, crankish, cubbish, cultish, dampish, dandyish, darkish, deepish, devilish, dilettantish, dimmish, doggish, dollish, doltish, donnish, dronish, dullish, dumpish, duncish, duskish, dwarfish, elfish, elvish, faddish, faintish, fairish, fairyish, farmerish, fattish, feverish, fiendish, fivish, foolish, foppish, fortyish, freakish, frumpish, gargoylish, garish, gawkish, ghostish, ghoulish, girlish, gnomish, goatish, goodish, goyish, gravelish, grayish, greenish, grumpish, gypsyish, hawkish, haymish, heathenish, heavenish, hellish, hermitish, highbrowish, hoggish, homish, hooliganish, huffish, impish, islandish, ivorytowerish, jargonish, jingoish, kiddish, kittenish, klutzish, knavish, lakish, largish, larkish, latish, lavish, lickerish, lightish, liverish, longish, loobyish, loudish, loutish, lowbrowish, lumpish, magazinish, maidish, mannish, marish, mawkish, Micawberish, milksoppish, mimish, mirish, modish, monkish, moodish, mopish, mugwumpish, mulish, mumpish, murmurish, narrowish, nearish, newspaperish, nighish, nightmarish, noonish, novelettish, nudish, nunnish, oafish, ocherish, offish, ogreish, old-fogyish, oldmaidenish, orangeish, outlandish, owlish, paganish, palish, pansyish, papish, peacockish, pearlish, peckish, peevish, pettish, picayunish, piggish, pikerish, pinkish, pixieish, planish, pollyannaish, poltroonish, poorish, popish, poppycockish, prankish, priestish, priggish, prima-donnaish, prudish, puckish, pukish, puppyish, purplish, quackish, qualmish, raffish, rakehellish, rakish, reddish, ricketish, roguish, rompish, rowdyish, ruttish, saltish, sans-culottish, scampish, scarecrowish, schoolboyish, schoolgirlish, schoolish, schoolmarmish, schoolmasterish, schoolteacherish, selfish, sharkish, sharpish, sheepish, shrewish, sickish, sissyish, sixish, skittish, slavish, slenderish, slimmish, slobbish, sluggish, sluttish, smallish, snakish, snappish, snobbish, sorryish, sottish, sourish, spinsterish, spookish, squattish, squeamish, standoffish, startlish, stillish, stylish, swampish, sweetish, swinish, sylphish, tartish, Tartuffish, teacherish, teenish, thievish, thinnish, ticklish, tigerish, toadish, toadyish, tomboyish, trickish, typhoonish, uppish, up-to-datish, vagabondish, vampirish, vandalish, vaporish, vinegarish, viperish, vixenish, voguish, waggish, warmish, waspish, waterish, wettish, whirlwindish, whitish, whorish, widowish, wimpish, wingish, wolfish, womanish, yellowish, yokelish, youngish, zombiish

In some cases there is spelling variation, e.g. blue-ish besides bluish, and in some cases the hyphen is obligatory, as in infrequent forms like beige-ish.

An isolated example where -ish is attached to a personal pronoun:

– “I patted my face, my shoulders, the girls, a.k.a. Danger and Will Robinson.

Yep, I felt very me-ish.” (Darynda Jones: Summoned to Thirteenth Grave, St. Martin’s Press, 2019)

注释

1In some cases there is spelling variation, e.g. blue-ish besides bluish, and in some cases the hyphen is obligatory, as in infrequent forms like beige-ish.

2An isolated example where -ish is attached to a personal pronoun:

– “I patted my face, my shoulders, the girls, a.k.a. Danger and Will Robinson.

Yep, I felt very me-ish.” (Darynda Jones: Summoned to Thirteenth Grave, St. Martin’s Press, 2019)

3The suffix is apparently so useful that it occasionally is even used on its own, as in the following example from modern English fiction:

(i) From: Lisa Jewell –Then She Was Gone(2018, Atria Books):

– “Yes. Kate Virtue. She’s nice. I like her. She’s not very clever, but she’s very sweet and kind.”

– “And SJ? Are you two close?”

– “Ish. I mean, we’re very different.”

The suffix appears as a book title: Ish, by Peter H. Reynolds (2004, Candlewick Press). See also example (23) in Eitelmann, Haugland & Haumann (2020: 816), taken from the BNC, and Norde (2009: 224-5).

4See Michel et al. (2011) for further information on Google Ngrams. Other graphs displaying lexical development from the same source will be presented below.

5https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?smoothing=3&corpus=26&content=soonish& year_end=2019& year_start=1800&direct_url=t1%3B%2Cuppish%3B%2Cc0#t1%3B%2Cuppish%3B%2Cc0 (last accessed August 12, 2020).

6An anonymous reviewer notes that other Germanic languages have a similar adjective which more clearly derives from the noun, e.g. German diebisch (from Dieb ‘thief’) or Norwegian tyvisk (from tyv ‘thief’). This is interesting but does not bear on the arguments advanced here that English thievish is not derived in a similar way.

7See below for discussion of this adjective (and the language Dwarvish) in Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings.

8https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=elvish%2C+elfish&year_start=1700&year_end=2000& corpus=29&smoothing=3 (last accessed August 12, 2020).

9https://www.imdb.com/title/tt00000000000029583/ (last accessed August 17, 2020).

10https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0120737/ (last accessed August 17, 2020).

11https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=dwarfs_NOUN%2C+dwarves_NOUN&year_start= 1800&year_end=2000&corpus=29&smoothing=3 (last accessed August 12, 2020).

12Note that in LOTR Tolkien usedelvishanddwarvishboth for the name of the language (e.g.Elvish tongue, Elvish script, Dwarvish) and for the characteristics of these peoples (e.g.elvish armour, elvish robes, dwarvish racket, dwarvish foot).

13Note that, conceivably, the spelling wolfish could in some cases correspond to a pronunciation with [v] (thanks to an anonymous reviewer for pointing this out) (cf. examples likepalsywherecorresponds to [-lz-]); however, there are no cases, at least in modern-day English, wherecorresponds to [-lv-](Jones et al. 2011).

14https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=wolvish%2C+wolfish&year_start=1700&year_end= 2000&corpus=29&smoothing=3 (last accessed August 12, 2020).

15This is also suggested as a possibility by Harper (2001-2020); see15http://www.etymonline.com/index.php? allowed_in_frame=0& search=thievish (last accessed June 20, 2020).

16Definitions from dictionary.com. All example sentences are from Google Books (last accessed June 20, 2020).

17Obsolete or more doubtful examples include wearish ‘withered, tasteless, puny’,garish(Eitelmann, Haugland & Haumann 2020: 803), which may be related to the obsolete Middle English verbgawren‘to stare’ (Harper 2001-2020), and perhapslavish(ultimately related to Latin lavare ‘to wash’) andpettish(>to pet‘to sulk’) (ibid.).

18Used in Lewis Carroll’s famous Jabberwocky poem (1871), “Come to my arms, my beamish boy!”: see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jabberwocky (last accessed June 20, 2020)

19Example from Eitelmann, Haugland & Haumann (2020: 826 (ex. 39b)).

20Thanks to an anonymous reviewer for bringing up this point.

References

Algeo, John. 1991. Fifty years among the new words. A dictionary of neologisms. Introduction. In John Algeo & Adele S. Algeo (eds.),Fifty yearsamong the new words. A dictionary of neologisms, 1-18. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Anderson, Stephen R. 1992.A-morphous morphology(Cambridge Studies in Linguistics 62). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Aronoff, Mark & Kirsten A. Fudeman. 2011.What is morphology?, 2nd edn (Fundamentals of Linguistics). Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Bauer, Laurie, Rochelle Lieber & Ingo Plag. 2013.The Oxford referenceguideto English morphology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Booij, Geert E. & Matthias Hüning. 2014. Affixoids and constructional idioms. In Ronny Boogaart, Timothy Colleman & Gijsbert Rutten (eds.),Extending the scope of Construction Grammar(Cognitive Linguistics Research 54), 77-106. Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Campbell, Alistair. 1959.Old English grammar. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Carstairs, Andrew. 1987. Diachronic evidence and the affix-clitic distinction. In Anna Giacalone Ramat, Onofrio Carruba & Giuliano Bernini (eds.),Papers from the 7th International Conference on Historical Linguistics(Current Issues in Linguistic Theory 48), 151-62. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Davies, Mark. 2004. BYU-BNC: The British National Corpus.

Davies, Mark. 2008. Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA): 410+ million words, 1990-present.

Dixon, R. M. W. 2014.Making new words: Morphological derivation in English. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dixon, R. M. W. & Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald (eds.). 2002.Word: A cross-linguistic typology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Eitelmann, Matthias, Kari E. Haugland & Dagmar Haumann. 2020. Fromengl-isctowhatever-ish: A corpus-based investigation of-ishderivation in the history of English.English Language and Linguistics24.4, 801-31.

Frisch, Stefan A. 2018. Exemplar theories in phonology. In S. J. Hannahs & Anna R. K. Bosch (eds.),The Routledge handbook of phonological theory, 553-68. London: Routledge.

Gerlach, Birgit. 2002.Clitics between syntax and lexicon(Linguistics Today 51). Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Halpern, Aaron L. 1998. Clitics. In Andrew Spencer & Arnold M. Zwicky (eds.),The handbook of morphology(Blackwell Handbooks in Linguistics), 101-22. Oxford: Blackwell.

Harper, Douglas. 2001-2020. Etymonline. http://www.etymonline.com.

Haspelmath, Martin & Andrea D. Sims. 2010.Understanding morphology, 2nd edn (Understanding Language Series). London: Hodder.

Horn, George M. 2003. Idioms, metaphors and syntactic mobility.Journal of Linguistics39.2, 245-73.

Janda, Richard D. & Brian D. Joseph. 1989. In further defense of a non-phonological account for Sanskrit root-initial aspiration alternations.Proceedingsofthe 5th Eastern States Conference on Linguistics, 246-60. Ohio State University.

Jespersen, Otto. 1933 [2008]. Voiced and voiceless fricatives in English. In Otto Jespersen (ed.),Selected writings of Otto Jespersen, 301-24. Abingdon and New York: Routledge.

Jones, Daniel, Peter Roach, Jane Setter & John Esling. 2011.Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary, 18th edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Joseph, Brian D. & Richard D. Janda. 1986. E pluribus unum: The rule constellation as an expression of formal unity amidst morphological fragmentation. Proceedings of the Milwaukee Morphology Meeting (Fifteenth Annual UWM Linguistics Symposium).

Kenesei, István. 2007. Semiwords and affixoids: The territory between word andaffix. Acta Linguistica Hungarica54.3, 263-93.

Kipfer, Barbara Ann & Robert L. Chapman. 2001.Roget’s international thesaurus, 6th edn. New York: HarperCollins.

Klavans, Judith L. 1985. The independence of syntax and phonology in cliticization.Language61.1, 95-120.

Lieber, Rochelle. 1982. Allomorphy.Linguistic Analysis10, 27-52.

Malkiel, Yakov. 1977. Why ap-ish but worm-y? In Paul J. Hopper (ed.),Studies in descriptive and historical linguistics(Current Issues in Linguistic Theory 4), 341-64. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Marchand, Hans. 1969.The categories and types of present-day English word-formation: A synchronic-diachronic approach, 2nd edn. Munich: Beck.

Michel, Jean-Baptiste, Yuan Kui Shen, Aviva Presser Aiden, Adrian Veres, Matthew K. Gray, Joseph P. Pickett, . . . Jon Orwant. 2011. Quantitative analysis of culture using millions of digitized books. Science 331.6014, 176-82.

Nida, Eugene A. 1949.Morphology: The descriptive analysis of words, 2nd edn (University of Michigan Papers in Linguistics 2). Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Norde, Muriel. 2009.Degrammaticalization(Oxford Linguistics). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nunberg, Geoffrey, Thomas Wasow & Ivan Sag. 1994. Idioms.Language70.3, 491-538.

Partridge, Eric. 1977. Origins;A short etymological dictionary of Modern English. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Plag, Ingo. 2003.Word-formationin English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Plag, Ingo, Christiane Dalton-Puffer & R. Harald Baayen. 1999. Morphological productivity across speech and writing.English Language and Linguistics3.2, 209-28.

Procter, Paul. 1978.Longman dictionary of contemporary English. Harlow: Longman.

Simpson, John A. & Edmund Simon Christopher Weiner. 1989.The Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edn. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Sykes, J. B. 1982. The conciseOxford dictionary of current English, 7th edn. Oxford: Clarendon.

Traugott, Elizabeth Closs & Graeme Trousdale. 2013.Constructionalization and constructional changes(Oxford Studies in Diachronic and Historical Linguistics 6). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Woodbury, Anthony C. 1996. On restricting the role of morphology in Autolexical Syntax. In Eric Schiller, Elisa Steinberg & Barbara Need (eds.),Autolexical Theory(Trends in Linguistic Studies and Monographs 85), 319-63. Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Zwicky, Arnold M. & Geoffrey K. Pullum. 1983. Cliticization vs. inflection: Englishn’t. Language59.3, 502-13.

责编丨翁冰莹

审核丨彭宣维

美编丨外国语学院融媒体中心 张栩曼